Department of Health and Human Services

DEPARTMENTAL APPEALS BOARD

Appellate Division

Borgess Medical Center

Docket No. A-19-19, A-19-20

Decision No. 3106

FINAL DECISION ON REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DECISION

These related appeals arise from a June 5, 2015 reconsidered determination by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that three physicians' clinics purportedly owned and operated by Borgess Medical Center (Borgess),1 an acute care hospital, did not meet the public awareness requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4). The basis for that reconsidered determination was that exterior signs at the three clinics and Borgess's website did not clearly identify the clinics as outpatient departments of Borgess. The public awareness requirement, among others, had to be met in order for Borgess, a Medicare-participating provider, to treat the clinics as "provider-based" (that is, as parts of the hospital) for Medicare payment purposes.

On September 11, 2018, an administrative law judge (ALJ) sustained the reconsidered determination, holding that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement "prior to October 2, 2015." Borgess Med. Ctr., DAB CR5185 (ALJ Decision). The ALJ further concluded that the clinics "met all requirements for provider-based status," including the public awareness requirement, "as of October 2, 2015," and that such status became "effective" on that date pursuant to 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(o). Id. at 1, 16.

Both parties have appealed the ALJ's decision. Borgess challenges only the part of the ALJ Decision unfavorable to it – namely, the ALJ's conclusion that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement before October 2, 2015. CMS challenges the ALJ's conclusion that the clinics met all requirements for provider-based status as of October 2, 2015 and that such status became effective on that date. CMS thus wants the Board to uphold only the ALJ's conclusion that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement before October 2, 2015.

Page 2

As we explain below, the issue before the ALJ was whether the three clinics met the public awareness requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4). The issues of when the clinics met the public awareness requirement and when they met all other requirements for establishing provider-based status were not before the ALJ. Accordingly, we conclude that the ALJ erred in reaching and deciding the "effective date" of the clinics' meeting the public awareness requirement and all other provider-based status requirements. We affirm only the ALJ's conclusion that the three clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4) before October 2, 2015; we vacate the ALJ's conclusion that the three clinics met all provider-based status requirements as of October 2, 2015. Our vacating the ALJ Decision in part effectively results only in a conclusion that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4).

Legal Background

A. Provider-based entities and billing

The Medicare program pays participating hospitals and other healthcare "providers" for health care services they furnish to program beneficiaries. Social Security Act (Act) §§ 1811, 1812(a) (providing that Medicare program benefits include payment for inpatient hospital services); 42 C.F.R. Part 419 (establishing prospective payment systems for hospital outpatient department services); 42 C.F.R. § 400.202 (defining the term "provider," for Medicare program purposes, to include hospitals).

For Medicare payment purposes, CMS recognizes that a hospital may own and operate other types of healthcare facilities or organizations, such as physicians' offices, that are located on or off the hospital's campus. See Final Rule, 65 Fed. Reg. 18,434, 18,504 (April 7, 2000). Subject to various statutory and regulatory limitations and conditions, CMS permits a hospital to treat such subordinate entities as "provider-based," and to bill their services to Medicare as outpatient hospital services. See id.; Shady Grove Adventist Hosp., DAB No. 2221, at 3 (2008) (citing Proposed Rule, 63 Fed. Reg. 47,552, 47,587-88 (Sept. 8, 1998)), aff'd sub nom. Adventist Healthcare, Inc. v. Sebelius, AW-09-00559, 2010 WL 3038917 (D. Md. July 30, 2010).2

Page 3

For some services, provider-based billing may result in Medicare payment exceeding what the program would pay for the same services if they were furnished in a "free-standing" facility or organization (that is, an entity not integrated with, or part of, a provider).3 Shady Grove at 3. Provider-based billing "may also serve to increase the coinsurance liability of Medicare beneficiaries who receive covered services in [the provider-based] facility." Id.

Prior to 2000, the Medicare program's criteria for designating a facility or organization as provider-based were found largely in Program Memorandum (PM) A-96-7, issued by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), CMS's predecessor. 65 Fed. Reg. at 18,504; Shady Grove at 15.

B. Regulatory requirements for provider-based status (42 C.F.R. § 413.65)

In 2000, CMS promulgated 42 C.F.R. § 413.65, which superseded PM A-96-7 and established requirements for a facility or organization to qualify for "provider-based status." 65 Fed. Reg. at 18,504.

The Act does not define the term "provider-based." However, section 413.65 defines "provider-based status" to mean the "relationship between a main provider and a provider-based entity or a department of a provider, remote location of a hospital, or satellite facility, that complies with the provisions of this section." 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(a)(2) (italics added). The term "main provider" is defined as "a provider [such as a hospital] that either creates, or acquires ownership of, another entity to deliver additional health care services under its name, ownership, and financial and administrative control." Id. The term "department of a provider" (which covers the physician clinics at issue in this case) is defined in part as "a facility or organization that is either created by, or acquired by, a main provider for the purpose of furnishing health care services of the same type as those furnished by the main provider under the name, ownership, and financial and administrative control of the main provider, in accordance with the provisions of this section [413.65]." Id. The regulation defines the term "provider-based entity," in part (and similar to the term "department of a provider"), as "a provider of health care services . . . that is either created by, or acquired by, a main provider for the purpose of furnishing health care services of a different type from those of the main provider under the ownership and administrative and financial control of the main provider . . . ." Id. A provider and its subordinate facility (i.e., its "department of a provider" or "provider-based entity") could achieve cost savings by "shar[ing] overhead costs and . . . revenue-producing assets." Shady Grove at 3.

Page 4

Section 413.65 distinguishes a facility or organization qualifying for provider-based status from a "[f]ree-standing facility." 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(a)(2). The latter is "an entity that furnishes health care services to Medicare beneficiaries and that is not integrated with any other entity as a main provider, a department of a provider, remote location of a hospital, satellite facility, or a provider-based entity." Id.

C. The "public awareness" requirement of section 413.65

Under 42 C.F.R. § 413.65, a facility or organization seeking provider-based status must meet all applicable requirements in that section concerning licensure, integration of clinical services, integration of financial operations, and "public awareness." 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d).4 The "public awareness" requirement at issue in this case is found in section 413.65(d)(4), which states:

Public awareness. The facility or organization seeking status as a department of a provider, a remote location of a hospital, or a satellite facility is held out to the public and other payers as part of the main provider. When patients enter the provider-based facility or organization, they are aware that they are entering the main provider and are billed accordingly.[5]

In the preamble to its 2000 rulemaking, CMS emphasized that an "objective in issuing specific criteria for provider-based status [was] to ensure that higher levels of Medicare payment and increases in beneficiary liability for deductibles or coinsurance (which can all be associated with provider-based status) are limited to situations where the facility or organization is clearly and unequivocally an integral and subordinate part of a provider." 65 Fed. Reg. at 18,506. CMS also commented that the public awareness requirement was "needed to help ensure that beneficiaries are protected from unexpected deductible and coinsurance liability." Id. at 18,522.

D. The 2002 amendments to section 413.65

As originally promulgated, section 413.65(b) prohibited a main provider from billing Medicare for a facility's services as provider-based unless the provider first applied for

Page 5

and obtained a determination by CMS that the facility was provider-based. 65 Fed. Reg. at 18,538. In order "[t]o provide an administrative appeals process" to contest a denial by CMS of an application for provider-based status, the 2000 rulemaking revised the list of appealable "initial determinations" in 42 C.F.R. § 498.3 to include, as specified in paragraph (b)(2), "determinations with respect to . . . [w]hether a prospective department of a provider, remote location of a hospital, satellite facility, or provider-based entity qualifies for provider-based status under § 413.65 of this chapter." Id. at 18,505, 18,524, 18,549. The 2000 rulemaking also revised section 498.3(b)(2) to include a "determination" by CMS about "whether . . . a facility or entity currently treated" as provider-based "no longer qualifies for that status under § 413.65 of this chapter." Id. at 18,524, 18,549.

In 2002, CMS amended section 413.65 by removing the requirement (in paragraph (b)) that a provider apply for and obtain a determination by CMS of a facility's or organization's provider-based status before billing its services as provider-based. The 2002 amendments substituted a voluntary process under which a provider may obtain a determination of provider-based status by submitting to CMS an "attestation" that the affiliated facility or organization meets all applicable requirements for that status. CMS then may use that submission to "make a determination as to whether the facility or organization is provider-based." 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(b)(3); see also 67 Fed. Reg. 49,982, 50,084-85, 50,087, 50,114-15 (Aug. 1, 2002). Thus section 413.65, as amended in 2002, does not require the main provider to obtain a determination of a subordinate facility's provider-based status before billing that facility's services as provider-based, but the provider's belief that the facility is provider-based does not legally entitle the provider to treat it as such for Medicare billing and payment purposes. 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(b)(1) (providing that "[a] facility or organization is not entitled to be treated as provider-based simply because it or the main provider believe[s] it is provider-based").

Section 413.65(j) – titled "Inappropriate treatment of a facility or organization as provider-based" – specifies how CMS is to handle such inappropriate treatment. Section 413.65(j) provides that if CMS (1) learns that a provider has treated as provider-based a facility or organization for which the provider did not request a determination of provider-based status using the voluntary attestation process, and (2) "determines that the facility or organization did not meet the requirements for provider-based status," then "CMS will":

- notify the provider "that payments for past cost reporting periods may be reviewed and recovered" and "that future payments for services in or of the facility or organization will be adjusted";

- "adjust the amount of future [Medicare] payments to the provider for services of the facility or organization" (that had been inappropriately treated as provider-based) based on an estimate of the "amounts that would be paid for

Page 6

the same services furnished by a freestanding [non-provider-based] facility";

- "recover [subject to certain limitations] the difference between the amount of payments that actually was made" for services at the facility or organization inappropriately treated as provider-based, and "the amount of payments that CMS estimates should have been made, in the absence of compliance with the provider-based requirements, to that provider for services at the facility or organization for all cost reporting periods subject to reopening . . ."; and

- "continue payments to the provider for services of the facility or organization" inappropriately treated as provider-based "only in accordance with" paragraph (j)(5).

42 C.F.R. § 413.65(j)(1)(i)-(ii), (j)(3), (j)(4), (j)(5). These provisions superseded the provisions of section 413.65(j), as promulgated in 2000, which specified certain consequences if a provider improperly treated a facility as provider-based without first having obtained CMS's approval of that status. 65 Fed. Reg. at 18,540-41.

Section 413.65(j)(5), titled "Continuation of payment," clarifies the circumstances under which Medicare payment for a facility's or organization's services will or will not continue after issuance of a "notice of denial of provider-based status" (that is, a notice to the provider that it has inappropriately treated the facility or organization as provider-based). The notice of denial of provider-based status will ask the provider to notify CMS within 30 days if the provider intends to seek a CMS determination of provider-based status or if the facility or organization intends to enroll in Medicare as a freestanding facility. 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(j)(5)(i). If the provider so notifies CMS, then Medicare payments for the facility's or organization's services will continue (in "adjusted" amounts applicable to a freestanding facility, as specified in section 413.65(j)(4)) for not longer than six months, under several additional conditions. Id. § 413.65(j)(5)(iii). Those conditions for continuing payment are met if "the provider or the facility or organization or its practitioners":

(A) Submits, as applicable, a complete request for a determination of provider-based status or a complete enrollment application and provide[s] all other required information within 90 days after the date of notice [of CMS's denial of provider-based status]; and

(B) Furnishes all other information needed by CMS to make a determination regarding provider-based status or process the enrollment application, as applicable, and verifies that other billing requirements are met.

Id. "If the necessary applications or information are not provided, CMS will terminate all

Page 7

payment to the provider, facility, or organization as of the date CMS issues notice that necessary applications or information have not been submitted." Id. § 413.65(j)(5)(v).

In short, under the process established by section 413.65(j), if CMS determines that a provider has inappropriately treated a subordinate facility or organization as provider-based, then CMS will not regard the facility or organization as provider-based for Medicare payment purposes unless or until the provider files an application or attestation requesting that CMS determine the facility's or organization's entitlement to provider-based status.

The effective date of any determination by CMS to approve a request for provider-based status is governed by section 413.65(o). Paragraph (2) of that section states that "if a facility or organization is found by CMS to have been inappropriately treated as provider-based under paragraph (j) of this section," then "CMS will not treat the facility or organization as provider-based for payment purposes until CMS has determined, based on documentation submitted by the provider, that the facility or organization meets all requirements for provider-based status." 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(o)(2). Paragraph (2) of section 413.65(o) is an application of the general rule in paragraph (1), which states that "[p]rovider-based status for a facility or organization is effective on the earliest date all of the requirements [for such status] have been met." Id. § 413.65(o)(1).

E. CMS's 2003 issuance of sub-regulatory guidance

In 2003, CMS issued PM A-03-030, which states that it superseded program instructions in two other CMS program manuals and "provides information on the background of the provider-based regulations [as revised in 2002] and notifies [Medicare program contractors] of the actions [they] are to take to implement the revised regulations." CMS Ex. 19, at 1. PM A-03-030 contains the following passage regarding the public awareness requirement:

As documentation [of compliance with section 413.65(d)(4)], the provider may maintain examples that show that the facility is clearly identified as part of the main provider (i.e., a shared name, patient registration forms, letterhead, advertisements, signage, Web site). Advertisements that only show the facility to be part of or affiliated with the main provider's network or healthcare system are not sufficient.

Id. at 6 (italics omitted).

Page 8

Case Background

Borgess is a Medicare-participating acute-care hospital located in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Joint Stipulations of Fact (Jt. Stip.) ¶¶ 1-3; Borgess Request for Review (B. RR) at 1. At all times relevant to the parties' dispute, Borgess was part of a healthcare network known as "Borgess Health" (or "Borgess Health Alliance"). Jt. Stip. ¶ 3; Borgess Exhibit (B. Ex.) 18; B. Ex. 24, ¶ 4. Borgess Health also included an entity named ProMed Healthcare. B. Ex. 24, ¶ 5; CMS Ex. 18, at 30; B. Ex. 18, at 1-2 (screenshot of Borgess Health website listing various "Borgess Corporate Entities," including ProMed Healthcare, Inc.).

In 2009 and 2010, Borgess began to treat certain off-campus physician clinics named "ProMed Physicians Family Practice" as provider-based for Medicare billing purposes. See Jt. Stip. ¶¶ 6-7. The clinics in question were located in Mattawan, Richland, Three Rivers, and Portage, Michigan. Id. ¶ 6. Borgess treated the clinics as provider-based without first having sought a determination from CMS that they qualified as such. Id. ¶ 7; B. Ex. 10, ¶ 15.

In 2014, CMS undertook to determine whether the ProMed Physicians clinics in Mattawan, Richland, Three Rivers, and Portage met the public awareness requirement and other requirements for provider-based status. CMS's investigation was prompted by a Medicare beneficiary's complaint that he had unexpectedly received a hospital bill after visiting a physician at one of the clinics. See CMS Ex. 1, at 4; CMS Ex. 2, at 2-3.

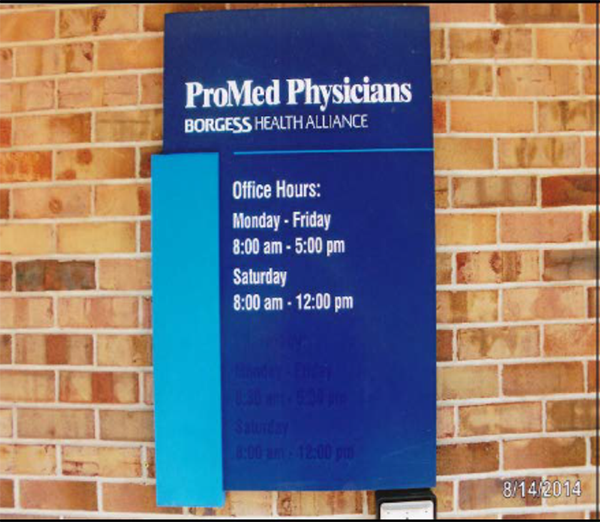

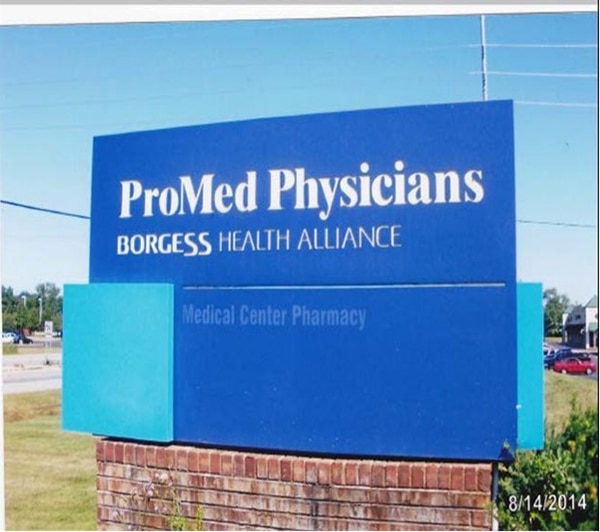

In assessing whether the clinics were compliant with the public awareness requirement, CMS examined, among other material, the clinics' exterior signs and Borgess Health's website. See CMS Exs. 3-6 (Aug. 2014 photographs); CMS Ex. 7 (September 4, 2014 Borgess Health webpage containing information about "ProMed Physicians – Family Practice," describing the practice as an "affiliate of Borgess Health," and listing the Mattawan, Portage, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics and their addresses). In August 2014, the clinics' exterior signs appeared as follows:

Page 9

Mattawan Clinic (CMS Ex. 3)

Page 10

Mattawan Clinic (CMS Ex. 3)

Page 11

Richland Clinic (CMS Ex. 4)

Page 12

Three Rivers Clinic (CMS Ex. 5)

***The top two lines of the sign near the door read:

ProMed Physicians

BORGESS HEALTH ALLIANCE

Page 13

Three Rivers Clinic (CMS Ex. 5)

Page 14

Three Rivers Clinic (CMS Ex. 5)

Page 15

Portage Clinic (CMS Ex. 6)

Page 16

Portage Cinic (CMS Ex. 6)

Page 17

Portage Clinic (CMS Ex. 6)

Page 18

As these photographs (taken in August 2014) reflect, signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics identified them as part of "Borgess Health," "Borgess," or "Borgess Health Alliance." CMS Ex. 3-5. Two of the three signs outside the Portage clinic, and building lettering, identified that clinic as part of "Borgess Woodbridge Hills," a campus of offices or facilities providing pharmacy, outpatient surgery, and other medical or healthcare services. CMS Ex. 6, at 1, 3. One photograph of the signage outside the Portage clinic does not show "Borgess," "Borgess Health," or "Borgess Health Alliance." Id. at 2.

A. CMS's initial determination under 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(j)(1)

On September 19, 2014, CMS issued an initial determination notifying Borgess that it had not met two requirements for treating the ProMed Physicians clinics in Mattawan, Richland, Three Rivers, and Portage, Michigan as provider-based. CMS Ex. 2. The two requirements were: the public awareness requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4); and the notice-of-coinsurance-liability requirement in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(g)(7). Id. (The latter requirement is not at issue in this case.)

In support of its finding that Borgess had not met the public awareness requirement, CMS stated, in relevant part:

The ProMed Physicians Family Practice locations are not sufficiently held out to the public as departments of Borgess Medical Center in Kalamazoo, Michigan (i.e., the hospital that claims these clinics as having provider-based status to it). The public awareness criterion for having provider-based status requires that patients who enter a provider-based department are aware that they are entering the main provider. Rather than being held out as departments of Borgess Medical Center, they are held out as "ProMed Physicians" and "Borgess Health." The signage for these facilities in no way indicates that they are part of Borgess Medical Center, the specific hospital located in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

The Borgess Health System is comprised of three separately-certified Medicare hospitals and a large number of other healthcare facilities. In order to satisfy the public awareness criterion, a provider-based department, remote location, or satellite facility must be held out to the public as part of the specific hospital that is the main provider. Signage indicating that the physician office is "ProMed Physicians" and "Borgess Health" only implies that the [ProMed Physicians] offices are associated with the Borgess Health system. Proper signage is vitally important to identify a healthcare facility as a provider-based hospital department and to satisfy the public awareness criterion. The "ProMed Physicians" and "Borgess Health" signage does not meet the requirement . . . .

Page 19

The Borgess website . . . does not help to clarify that the "ProMed Physicians" locations are departments of a hospital. The website merely identifies the ProMed clinics as "affiliates" of Borgess Health [referring to the website screenshot in CMS Ex. 2, at 6], again only implying that the practices are associated with the health system and not an integrated part of one of the three Borgess hospitals. The description of the family practice clinics in no way indicates that the facilities are anything other than freestanding physician offices.

The public awareness requirement . . . is important and applies to all provider-based departments, remote locations, and satellite facilities. Medicare patients generally face higher cost-sharing obligations at provider-based departments when compared with a freestanding facility offering the same healthcare services. The main provider's requirement to represent these facilities as a part of the main provider informs patients that they are entering a hospital and permits them to make informed decisions about their health care prior to receiving services.

CMS Ex. 2, at 2 (italics added).

Based on the noncompliance findings, the initial determination notified Borgess of the remedies CMS was imposing and Borgess's responsive options. CMS would, in accordance with 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(j)(1)(ii), "recover overpayments made from [September 19, 2014] back to the date on which [Borgess] began inappropriately treating the [four ProMed clinics] as provider-based." Id. at 3. Borgess had three options for clarifying or resolving the clinics' status with the Medicare program:

- Option 1 – "notify CMS in writing within 30 days . . . that [it] intends to make the changes needed for the [clinics] to comply with the provider-based rules" and that it "intends to seek a determination of provider-based status for [the clinics]";

- Option 2 – "notify CMS in writing within 30 days . . . that the [clinics] (or . . . the practitioners who staff [them]) will be seeking to enroll and meet other requirements to bill for services in a freestanding facility"; and

- Option 3 – "choose not to notify CMS" with respect to the other two options, in which case "all payment [would] end as of the 30th day after the date of the notice."6

Page 20

Id. at 3-4. If Borgess elected Option 1, Medicare would continue to pay for the clinics' services at rates applicable to freestanding facilities (but for no longer than six months), provided that Borgess submitted a "complete request (not an attestation) for a provider-based determination and all other required information within 90 days," and that "[i]f the necessary application or information [was] not provided, CMS [would] terminate all payment . . . as of the date CMS issue[d] notice that necessary applications or information ha[d] not been submitted." Id. at 3. Regardless of which option Borgess chose, it could appeal the "denial of provider-based status" in accordance with the procedures in 42 C.F.R. Part 498. Id. at 4.

By letter dated November 5, 2014, Borgess informed CMS that it had elected Option 1. CMS Ex. 31, at 1. Borgess stated that it would "work with [CMS] to obtain approval of signage and branding that will satisfy the provider-based requirements and then submit a determination request for approval of provider-based status for" the four ProMed Physicians clinics. Id. Borgess also notified CMS that it would "separately file a Request for Reconsideration . . . seeking a redetermination of the revocation of provider-based status for the [clinics]." Id. at 2.

B. Borgess's reconsideration request and post-request correspondence, and CMS's reconsidered determination

On December 4, 2014, Borgess filed a request for reconsideration, asserting that it had not violated either the public awareness or the notice-of-coinsurance-liability requirement, and that the four clinics in question were "clearly integrated with the Hospital [Borgess Medical Center] and held out to the public as part of the hospital." CMS Ex. 32, at 1-2.

With respect to the public awareness requirement, Borgess contended that the clinics' exterior signs adequately communicated that the clinics were part of the hospital. Borgess emphasized that all of the signs contained the name "Borgess"; that "the public generally associates [that name] with the Hospital"; that the "addition of the words Health or Health Alliance to the word Borgess does not negate the impact of the use of the Borgess logo and identification of that as a hospital within the Kalamazoo [Michigan] market." Id. at 3-5. Borgess also emphasized that the Portage clinic's exterior signs used only the name "Borgess" and thus any concern CMS harbored about the names "Borgess Health" and "Borgess Health Alliance" was irrelevant in judging whether that particular clinic met the public awareness requirement. Id. at 5.

Borgess further contended that the absence of the words "Medical Center" adjacent to the "Borgess" name on the clinics' exterior signs was not "solely determinative," and that the clinics' compliance could be demonstrated by showing that they provided patients (either in-person or online) with other material identifying them as parts of the hospital. Id. at 3, 5. In support of these contentions, Borgess relied upon Johns Hopkins Health Systems,

Page 21

DAB CR598 (1999), aff'd, DAB No. 1712 (1999), which held that an oncology center that Johns Hopkins Hospital treated as provider-based had met the then-existing public awareness standard in PM A-96-7. Id. at 2-3. Borgess asserted that Johns Hopkins "demonstrates that a hospital does not necessarily need to use its entire name in order to meet the public awareness requirement" and "clearly indicate[s] that when evaluating the public awareness standard CMS must look to the record as a whole and should not pick and choose specific pieces of evidence." Id. at 3, 5.

As evidence that the clinics used means other than exterior signs to meet the public awareness requirement, Borgess submitted copies of three documents or notices allegedly provided, or made available, to patients inside the clinics. Id. at 5, 69-73. One document, titled "Important Notice," states: "As you may know, Borgess Medical Center owns and operates this physician office. To comply with Medicare regulations, we create two separate bills for your office visit. Specifically, we generate a bill for the physician and another bill for the facility. You will receive a separate Medicare explanation of benefits . . . for each." Id. at 73 (emphasis in original). The "Important Notice" further states that a patient's coinsurance responsibility might "change" (that is, increase) because of "this Medicare billing requirement" and gives examples of physician and "facility" charges (and associated coinsurance amounts) for a "common physician visit" in the clinic. Id. A second document, titled "Provider-Based Medicare Billing," poses the question, "What does Provider-Based Medicare billing mean?" and gives the following answer: "This is a Medicare status for hospital clinics that comply with specific Medicare regulations. As a result of this status, Borgess Medical Center will bill Medicare in two parts. You will receive bills from Borgess Medical Center [for a "facility fee"] and your physician office" (for the professional services of the physician or other practitioner). Id. at 71-72. The Provider-Based Medicare Billing notice also contains estimates of patient coinsurance amounts and includes the hospital's name and address at the bottom. Id. at 72. The third document is a form titled "General Consent for Treatment – Physician Office Practices and Off-Campus Departments." Id. at 69. The "Borgess" wordmark appears at the top of the consent form, and the form uses the name "Borgess" throughout. Id. at 69-70. In addition to these patient forms, Borgess provided with its reconsideration request screenshots of webpages from the Borgess website that listed numerous "Borgess Locations" – including "ProMed Physicians Family Practice" clinics in Mattawan, Richland, Three Rivers, and Portage – just below the Borgess wordmark and a photograph of the Borgess campus.7 Id. at 4, 64-68.

Page 22

On April 28, 2015, following up on a telephone conference between the parties, Borgess wrote to CMS about its plans to change the signs outside the ProMed Physicians clinics. CMS Ex. 34. Borgess attached to its April 28th correspondence a mockup of the modified signs and asked CMS for "input before any of the signs are installed." Id. at 1. Borgess also informed CMS that it had updated its website "to more clearly indicate that the clinics are operated as a part [of] the Hospital." Id.

On June 5, 2015, CMS issued a "partially unfavorable" reconsidered determination. CMS Ex. 1, at 1. CMS determined that the ProMed Physicians clinics in Mattawan, Richland, Three Rivers, and Portage met the notice-of-coinsurance-liability requirement. Id. at 3. CMS also determined that the Portage clinic met the public awareness requirement, stating: "Accepting [Borgess's] argument that local residents closely associate the stand-alone name ‘Borgess' with the hospital, we are persuaded that the primary and prominent use of the logo ‘Borgess' at the facility at 7901 Angling Road [see CMS Ex. 6] is – when considered with other evidence tying the facility to the main provider – sufficient to allow a finding that this particular facility is held out to the public as part of Borgess Medical Center." Id. However, for the following reasons, CMS upheld its initial determination that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not satisfy the public awareness requirement:

Unlike the Portage facility, the signage for [the Matawan, Richland and Three Rivers clinics] identifies them first and foremost as "ProMed Physicians" clinics and not as integral and subordinate parts of Borgess Medical Center. . . . [Before the Hospital began operating the ProMed clinics in Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers as provider-based], ProMed Physicians had a history of operating many freestanding physician clinics known to the people of the Kalamazoo area. The ProMed Physician clinics at issue here were treated as provider-based to Borgess Medical Center without sufficient re-branding to clearly identify that these clinics now operate and charge as hospital outpatient departments. It is possible that patients, who had seen their ProMed physicians in those freestanding physician offices, continued to see the same physicians, sometimes in the same offices, only now in a hospital outpatient setting. When well-known freestanding physician offices transition to provider-based hospital departments, CMS expects the main provider to ensure that this transition is clearly communicated to the public, including through signage identifying the facilities as now being an integrated part of a hospital, in this case Borgess Medical Center.

While the signage for [the Mattawan, Three Rivers, and Richland] facilities includes reference to "Borgess Health" or "Borgess Health Alliance," this is insufficient to clearly identify them as provider-based departments of their main provider, the hospital named Borgess Medical Center. While we have

Page 23

accepted [the] argument that Borgess Medical Center is known locally simply as "Borgess," it does not follow that use of any phrase that includes the word "Borgess" shows that a facility is sufficiently associated with Borgess Medical Center to satisfy the public awareness requirement.

In fact, Borgess Health is a sizable health system in southwest Michigan and is comprised of three separately-certified hospitals (Borgess Hospital, Borgess Lee Memorial Hospital, and Borgess Medical Center) and a number of other locations. Many health systems operate freestanding physician clinics. The term "Borgess Health Alliance," similarly refers to much more than the Borgess Medical Center alone. A provider-based location must hold itself out to the public as part of the main provider, not as part of a group that also includes the main provider. CMS has long-standing guidance, CMS Program Memorandum A-03-030, explaining that "only show[ing] the facility to be part of or affiliated with the main provider's network or healthcare system" is not enough to show the facility is "clearly identified as part of the main provider." Merely identifying the ProMed Physicians Family Practice facilities as part of the health system, or in alliance with the health system, does not identify them to the public as part of Borgess Medical Center specifically. In fact, a Medicare beneficiary visiting the Three Rivers Facility submitted a complaint and stated that he did not know he was receiving care in a hospital facility, which supports the conclusion that the signage, which is similar in all three ProMed Physicians Family Practice locations, is insufficient to alert a beneficiary that he or she is entering the main provider.

The Borgess Health website . . . did not clarify the relationship between the ProMed Physicians Family Practice and the hospital called Borgess Medical Center. The website information, which has since been updated, identified the facilities only as ProMed Physicians locations, with an indeterminate "affiliation" with the larger Borgess Health system, not specifically as part of Borgess Medical Center, the main provider.

Id. at 3-5. The reconsidered determination noted that Borgess had submitted information about changes it "plan[ned] to make to come into compliance with regulatory requirements" but that this information was "not relevant to the reconsideration" because it "cannot show the [clinics] met regulatory requirements at the applicable time" (that is, as of the date of the adverse determinations). Id. at 3. The reconsidered determination also advised Borgess that "further action w[ould] be taken" pursuant to 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(j)(1)(ii) to recover Medicare overpayments resulting from the inappropriate treatment of the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics as provider-based. Id. at 5. Finally, the reconsidered determination notified Borgess that it could, if dissatisfied with the result, request a hearing before an administrative law judge. Id.

Page 24

C. CMS's June 8, 2015 correspondence, Borgess's hearing request, and the proceedings before the ALJ

On June 8, 2015 (three days after it issued the reconsidered determination), CMS sent Borgess a letter responding to the latter's April 28th correspondence. B. Ex. 19. Cautioning that its letter was "intended as informal guidance only and . . . may not be relied upon to show compliance with any aspect of the provider-based status regulations," CMS stated that Borgess's modified signs for the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics "appear similar to the current signage at the Portage facility, a location that CMS has accepted as provider-based," and that "proposed changes to the branding and website content that have been completed for the ProMed Physicians sites appear to reflect that the ProMed Physicians Family Practice sites are operated as part of Borgess Medical Center." Id. at 2. Before providing its "informal guidance," CMS reminded Borgess, "in accordance with 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(o)(2)," that if it wished to treat the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics as provider-based, then it needed to "submit complete attestations of provider-based status for each facility," and CMS needed to determine, based on those submissions "and any associated material," that the facilities complied with "all of the provider-based requirements and obligations . . . ." Id. at 1.

On July 31, 2015, Borgess requested an ALJ hearing to challenge the "denial of provider-based status with respect for the" Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics. Jt. Stip. ¶ 14. Between November 2015 and March 2016, the parties exchanged documentary evidence and written legal argument. Among the exhibits proffered by Borgess were declarations by Richard Felbinger, Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of Borgess Health, who averred that Borgess Medical Center was founded in 1889 and has been located on the same campus since 1917; that "[d]ue to its long history and prominent role in the region, Borgess Medical Center is inextricably associated with the name ‘Borgess' throughout southwest Michigan"; and that Borgess Medical Center "is the flagship hospital of the Borgess Health system." B. Ex. 10, ¶ 5. Referring to the previously mentioned documentation submitted with Borgess's reconsideration request, Felbinger further averred that "every patient who sets foot" in the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics is presented with "multiple signs, forms, and documents" identifying the clinics as part of Borgess Medical Center. Id. ¶ 8. In particular, said Felbinger, "[a] version" of the "Important Notice" concerning Medicare billing for office visits (and stating that "Borgess Medical Center owns and operates this physician office") has been displayed on a sign "[a]t the reception desk" of the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics "since each began billing as provider-based," and that each clinic also makes available, as a "brochure," the "Provider-Based Medicare Billing" notice. Id. ¶¶ 9-11 (referring to CMS Ex. 32, at 71-73, and citing B. Exs. 3-5 (photographs of interior signs)). In addition, said Felbinger, "[b]efore receiving care" at any of the clinics, "patients are asked to read and sign [the] treatment consent form, both pages of which bear the Borgess wordmark," as well as a Notice of Privacy Practices containing that wordmark. Id. ¶¶ 12-13 (citing CMS Ex. 32, at 69-70 and B. Ex. 6).

Page 25

Before filing their opening briefs, the parties filed a Joint Stipulation of Facts, a Joint Statement of Issues Presented, and a Joint Settlement Status Report. In the Joint Settlement Status Report, the parties "waive[d] oral hearing and request[ed] a decision on the briefs and written record, including the evidence submitted as part of their respective pre-hearing exchanges." Jt. Settlement Status Rpt. at 1.

Borgess's opening brief to the ALJ (filed February 5, 2016) largely echoed or elaborated on points made in its request for reconsideration. Borgess contended that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics met the public awareness requirement in part because information available to patients inside the clinics "presented . . . clear explanations of the [clinics'] provider-based status before those patients received care," thereby "achiev[ing] CMS's stated goal in codifying" the public awareness requirement – namely, "protecting patients from unexpected deductible and coinsurance liability." Borgess Med. Ctr. (BMC) Opening Br. to ALJ at 2, 9-11. Borgess further contended that section 413.65(d)(4), PM A-03-030, and Johns Hopkins require CMS and administrative adjudicators to consider all relevant communications when determining whether the public awareness requirement is met – including efforts made inside a facility to inform patients about its relationship to the main provider – but that CMS failed to consider such efforts in this case. Id. at 10-11, 13-17, 20. In addition, Borgess argued that its website contained information from which a person "could easily infer" the "integration" of the clinics with Borgess Medical Center. Id. at 18-19 (citing B. Ex. 18).8

In its opening brief to the ALJ (filed on the same day as Borgess's), CMS urged the ALJ to affirm its "denial of provider-based status" for the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics, contending that the efforts of those clinics to hold themselves out as part of Borgess Medical Center fell short of meeting the public awareness requirement. CMS Opening Br. to ALJ at 2, 16, 23-24. The public awareness requirement was not met, said CMS, because the clinics' exterior signs did not disclose to the public that the clinics were part of Borgess Medical Center and at most "suggest[ed] a secondary affiliation to either ‘Borgess Health,' the health network to which Borgess Medical Center belongs, or ‘Borgess Health Alliance,' an undefined group that also includes Borgess Medical Center." Id. at 18. CMS further argued that the Borgess Health website did not (in 2014) clearly and unequivocally identify the clinics as outpatient departments of Borgess Medical Center, but merely as the hospital's "affiliates," a term that CMS said had been "used to describe the relationship between ProMed Physicians and Borgess Health network two years before Borgess Medical Center began treating the offices as provider-based." Id. at 13, 18 (italics in original) (citing CMS Exs. 7 and 11). In addition, CMS

Page 26

asserted that the word "public" in 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4) "demonstrates that CMS expects not only Medicare beneficiaries but also the public at large to be able to discern the relationship between the hospital and its outpatient departments." Id. at 18. CMS also argued that Johns Hopkins is not controlling, in part because it applied program guidance that section 413.65(d)(4) superseded. Id. at 22-23.

One week after the parties' opening briefs were filed, CMS objected to the admission of Borgess's Exhibits 12, 13, and 14.9 Those exhibits contain photographs of what Borgess said (in its opening brief) were "altered" signs that appeared outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics "as of October 2, 2015" – signs that included the name "Borgess Medical Center" – and invoices requesting payment for the signs' design, fabrication, and installation. See BMC Opening Br. to ALJ at 8. CMS argued in its motion that the three exhibits are irrelevant because the new signs were installed five months after CMS issued the reconsidered determination – a determination that, according to CMS, addressed only the clinics' "current and historical compliance" with the public awareness requirement. CMS Obj. to B. Exs. (filed Feb. 12, 2016) at 2-3. "Even if the new signs meet the public awareness requirement[ ] at 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4)," said CMS, "at most they are evidence of compliance with that single requirement" and "do not make it more or less probable that the [clinics] were in compliance with all provider-based regulations on the date CMS rendered its reconsideration decision." Id. at 3 (internal quotation marks omitted).

In response to CMS's motion, Borgess asserted that evidence concerning the new signs was "relevant and probative to the issue presented as it illustrate[d] Borgess's continuing efforts to adhere to CMS guidance" and "provide[d] an illustration of the Hospital's historic and current compliance efforts." BMC Br. in Support of Admission of B. Exs. 12-14 (filed March 3, 2016) at 3. Borgess further stated: "Given the issue presented, comparisons of the signage are directly relevant to the parties' competing arguments regarding the requirements to be met under the Public Awareness Standard." Id.

The ALJ's Decision

Although neither party indicated in its briefs to the ALJ that October 2, 2015 – the date by which Borgess had allegedly installed redesigned signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics – was legally relevant, the ALJ used that date to define the compliance issues under review. The ALJ stated that those issues were: (1) whether the three clinics met the public awareness requirement "prior to" October 2, 2015 (see ALJ Decision at 7-8); and (2) whether the clinics met that requirement – and all other requirements for provider-based status – "as of" October 2, 2015 (id. at 15).

Page 27

Before addressing those issues, the ALJ overruled CMS's objection to the admission of Borgess Exhibits 12, 13, and 14, stating that they were "highly relevant to demonstrate that [Borgess] was in compliance with all requirements for provider-based status as of October 2, 2015." Id. at 3. The ALJ also stated that the ALJ was "not limited to reviewing CMS's reconsidered determination to decide whether it was in error," and was "required to conduct a de novo review of the evidence to determine if and when [Borgess] met the provider-based requirements for the three facilities in issue." Id. at 16 (italics added, citing 42 C.F.R. § 498.3(b)(2)).

Addressing the first compliance issue, the ALJ began by examining section 413.65(d)(4)'s two-sentence text. Relying on the second sentence, the ALJ held that the regulation's "plain language" provides that patients, "as they ‘enter the provider-based facility or organization,'" must be "‘aware that they are entering the main provider'" so that "they can know that they will be billed as if at the main provider's campus," and that "[i]f patients are not aware that they are entering the main provider as they enter the [allegedly provider-based] facility or organization, [then] the facility or organization does not meet the public awareness requirement." ALJ Decision at 8 (quoting 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4)) & 11. Based on that understanding of the regulation, the ALJ assessed "what a patient or the public could have known about the three [ProMed clinics] upon entering them." Id. at 8. The ALJ found that the exterior signs for the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics, as they appeared in CMS's August 2014 photographs, "contain no reference to ‘Borgess Medical Center'" and thus it "was not possible for the public or a patient to determine upon entering the facilities" that an individual was entering Borgess Medical Center (the ostensible main provider). Id. (citing CMS Exs. 3-5). More specifically, the ALJ found it "more likely than not that patients entering the Richland location or the Three Rivers location [in August 2014] . . . would be aware only that they were entering an office of ProMed Physicians and that the office was a part of the Borgess Health Alliance, not that they were entering a facility operated by" Borgess Medical Center, and that "patients entering the Mattawan location at best would be confused whether that location was associated with [Borgess Medical Center] or Borgess Health" given that one of that clinic's signs displayed the name "Borgess" while the sign on the clinic's door displayed the name "Borgess Health." Id. at 9 (citing CMS Ex. 3, at 1).

In addition, the ALJ:

- found that information provided or available inside a clinic would not have "give[n] a patient notice that [Borgess] was the main provider until after the patient entered, which does not satisfy the requirement of 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4)" (id. at 11-12);

- rejected Borgess's contention that the purpose of section 413.65(d)(4) is satisfied as long as patients become aware that they have entered the main

Page 28

provider "prior to receiving care," stating that section 413.65(d)(4) "clearly requires that a patient be aware upon entry of the relationship between the main provider and provider-based facility," and that "[b]ecause the regulatory language is clear, there is no need to resort to tools for interpreting that language to mean something different from what it says" (id. at 11);

- found that Borgess's evidence, including results of a consumer survey, did not permit "any inferences about what the general public or patients entering the Mattawan, the Richland, or the Three Rivers locations for treatment might think when they saw the words ‘Borgess Health' or ‘Borgess Health Alliance' on the signs for those locations, rather than ‘Borgess Medical Center'" (id. at 12-14);

- found that the content of Borgess's website has "little probative value related to the issue of whether . . . patients were aware on entering any of the three locations that those locations were operated by [Borgess]" (id. at 9); and

- held that Borgess's reliance on Johns Hopkins was "misplaced" for a number of reasons, including the fact that the decision interpreted and applied program guidance that was superseded by the applicable regulation (id. at 11-13).

Based on the foregoing findings and reasoning, the ALJ concluded that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not meet section 413.65(d)(4)'s public awareness requirement "prior to October 2, 2015." Id. at 15.

Relying (apparently) on Borgess Exhibits 12-14, the ALJ further concluded that the clinics met the public awareness requirement "as of October 2, 2015" because, by that date, each had a new exterior sign "contain[ing] a stand-alone use of the ‘Borgess' wordmark and, more importantly, specifically list[ing] ‘Borgess Medical Center.'" Id.

Finally, the ALJ concluded that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics met all other requirements (besides the public awareness requirement) for provider-based status as of October 2, 2015, and therefore the "effective date" of the clinics' provider-based status was October 2, 2015. Id. at 15-16. In support of that conclusion, the ALJ stated:

In its September 19, 2014 initial determination, CMS cited only two requirements for provider-based status that it determined [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations did not meet – 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4) and (g)(7). In its June 5, 2015 reconsidered determination, CMS determined that [Borgess] and its locations did meet the requirement of 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(g)(7), but did not meet the other, 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4). I infer from these determinations that [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations met all other applicable

Page 29

requirements for provider-based status as of the date of the reconsidered determination [June 5, 2015]. I have concluded that as of October 2, 2015, [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations met the public awareness requirement of 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4). It follows, then, that as of October 2, 2015, [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations met the requirements for provider-based status.

. . . CMS is bound by its prior initial and reconsidered determinations that strongly support the inference that CMS determined that [Borgess] met all provider-based requirements other than 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4). Thus, my conclusion that [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations have shown that they met the requirement of 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d)(4) as of October 2, 2015, establishes that [Borgess] and the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers locations met all requirements for provider-based status as of that date.

Id. at 16 (record citations omitted, italics added).

Analysis

As noted in the introduction, both parties request Board review of the ALJ's decision: Borgess appeals the ALJ's conclusion that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015; CMS appeals the ALJ's conclusion that those clinics met the public awareness requirement, and all other applicable requirements for provider-based status, as October 2, 2015. We consider both appeals – beginning with Borgess's – under the same standard of review: we review the ALJ's findings of fact to determine if they are supported by substantial evidence, and review the ALJ's legal conclusions de novo. See Johns Hopkins, DAB No. 1712, at 2.

A. The ALJ's conclusion that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015 is supported by substantial evidence and consistent with the governing regulation.

Borgess's request for review restates or elaborates upon arguments made before the ALJ. Although our evaluation of those arguments differs in some respects from the ALJ's, we affirm the ALJ's conclusion that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015, because that conclusion is supported by substantial evidence and consistent with the governing regulation.

The ALJ concluded that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015 because their exterior signs at that time failed to identify the clinics as

Page 30

parts of Borgess Medical Center, the ostensible main provider. Substantial evidence supports the finding that the signs did not identify the clinics as part of Borgess Medical Center. As CMS's photographs reflect, the signs, which appeared near the clinics' entrance doors, did not include the main provider's name. In each instance, the sign identified the clinic first and foremost as "ProMed Physicians." CMS Ex. 3, at 1; CMS Ex. 4; CMS Ex. 5, at 1-3; see also CMS Ex. 8, at 1-2 (Google street views of Richland and Mattawan). Although the signs indicated, in smaller type below the ProMed Physicians name, that the clinics were part of the network of healthcare facilities known as "Borgess Health" or "Borgess Health Alliance," that information failed to convey that the clinics were parts of Borgess Medical Center because the Borgess Health network encompassed multiple types of healthcare facilities, including physician practices, not merely Borgess Medical Center.10 CMS Ex. 12.

The ALJ committed no legal error in concluding that these facts demonstrated noncompliance with the public awareness requirement. The ALJ construed section 413.65(d)(4) as requiring that a provider-based facility be identified in a way which makes patients aware "as they are entering" or "upon entering" the facility that it is part of the main provider. ALJ Decision at 8 (stating that the "regulation requires that as they enter the provider-based facility, . . . patients must be aware that they are entering the main provider" (internal quotation marks omitted)). That interpretation is not inconsistent with section 413.65(d)(4)'s second sentence, which states, as an apparent regulatory objective, that"[w]hen patients enter [a] provider-based facility or organization, they are aware they are entering the main provider . . . ." Borgess contends that the ALJ's construction of section 413.65(d)(4) "contravenes [the regulation's] plain language," B. Reply Br. at 2-3, but does not say how the ALJ's construction is incompatible with the regulation's text or specify a reasonable alternative construction that compels a conclusion different than the one the ALJ reached. The ALJ therefore did not err in concluding that the exterior signs' failure to identify the clinics as parts of Borgess Medical Center violated the public awareness requirement.

The ALJ's conclusion that the clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement is further supported by section 413.65(d)(4)'s first sentence, which states that a facility or organization meeting the public awareness requirement is one that is "held out to the public" (and to "other payers") as part of the main provider. The term "public" is commonly and ordinarily understood to mean the people or community "as a whole." Merriam Webster Online Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/public (defining the term as the "populace" or the "people as a

Page 31

whole"); accord Black's Law Dictionary 11th ed. 2019 (defining the term as "[t]he people of a country or community as a whole"). The clinics' exterior signs, located outside and facing the surrounding community, unquestionably held out the clinics to "the public." The signs therefore had to meet the regulatory standard established in the regulation's first sentence. The signs did not meet that standard because they did not identify the clinics as part of Borgess Medical Center, the main provider.

The clinics were also not "held out to the public" on Borgess's website (Borgess.com) as being parts of Borgess Medical Center (the hospital) prior to October 2, 2015, despite Borgess's contrary claims. See B. Opening Br. to ALJ at 17 (asserting that information on Borgess.com "supplemented the Hospital's Efforts to Meet the Public Awareness Standard"). Evidence in the record shows that the website (circa 2010 and 2014), like the signs, did not meet the regulatory standard because it identified the clinics, not as integral and subordinate parts of Borgess Medical Center, but as "affiliates" or components of the "Borgess Health" network. CMS Ex. 2, at 6 (September 4, 2014 Borgess.com webpage identifying "ProMed Physicians – Family Practice" as an "affiliate of Borgess Health"); CMS Ex. 13 (Borgessnews.com webpage containing a June 2010 notice identifying the Mattawan clinic as an "affiliate" of Borgess Health).

Borgess submits that a provider-based facility "should be considered to have met the public awareness standard if, taking into account all the information provided to a patient before receiving services," including information provided inside the facility, "a beneficiary would be aware that the facility is provider-based to a main provider and understands the financial implications of that relationship." B. RR at 18-19; id. at 6 (asserting that section 413.65(d)(4) can be "interpreted rationally" to require that CMS "tak[e] account of all information available to a prospective patient, prior to the time that he or she receives services at a provider-based department"). Based on that proposition, Borgess contends that the ALJ should have found the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics compliant with section 413.65(d)(4) based on unrefuted evidence that, once inside the clinics, and prior to receiving services, patients received information about the clinics' "provider-based relationship" with Borgess Medical Center and the financial "implications" or consequences of that relationship. Id. at 7-8; see also B. Reply Br. at 5 (asserting that the ALJ erred in failing to consider the "plethora of information conveyed to patients in the registration area inside the Clinics and prior to receipt of services"). Those materials included: the "Important Notice" concerning Medicare billing for office visits, which states, among other things, that "Borgess Medical Center owns and operates this physician office"; the Provider-Based Medicare Billing notice indicating that a patient of the clinic would receive bills from both Borgess Medical Center and the clinic; and a treatment consent form and privacy notice, both of which bore the Borgess wordmark. B. RR at 7-8 (citing CMS Ex. 32, at 69-73). In short, Borgess contends that the clinics were compliant with the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015 because, even if their exterior signs did not identify them as parts of Borgess

Page 32

Medical Center, information available or provided inside the clinics made patients aware that they had entered a part of that hospital.

We agree with Borgess that evidence about how a purportedly provider-based facility identifies itself to patients (and others) once they have entered may be probative of whether the facility meets the public awareness requirement; we disagree, however, that such evidence establishes Borgess's compliance in this case. Under Borgess's construction of section 413.65(d)(4), an off-campus provider-based facility may identify itself to the surrounding community (through exterior signage, advertising, or a website) as freestanding, or as something other than an integral and subordinate part of the main provider, but nonetheless satisfy the regulation by informing "patients" who have entered the facility that it is part of the main provider. B. Reply Br. at 3-5 (suggesting that any problems with the clinics' exterior signs are "not dispositive" if other communications "tie the facility to the main provider"); id. at 16 (alleging that information provided within its clinics helped to "clarif[y] any alleged ambiguity with the exterior signage, sufficient to meet the public awareness standard"). We see nothing in the regulation's text that permits, much less requires, the regulation to be applied in this way. If anything, Borgess's approach fails to give full effect to section 413.65(d)(4)'s first sentence, which on its face applies to any way in which a provider-based facility (or a facility that is treated as such) is "held out to the public." "The public" to whom a facility is "held out" includes not just those who enter the facility but persons outside the facility who are contemplating using its services or inquiring about available service providers, family members of patients, and others with financial or other responsibility for the care of the facility's patients. A facility treated as provider-based does not satisfy the standard in section 413.65(d)(4)'s first sentence when it identifies itself – by means intended or designed to reach the public (or "other payers") – as something other than a part of the main provider. Accepting Borgess's construction of the regulation would permit a facility to identify itself in conflicting or inconsistent ways and thereby confuse the community about its relationship to the main provider.

Borgess makes a host of other contentions or arguments, none of which persuades us that the ALJ's decision (so far as it concerns CMS's inappropriate-treatment determination under section 413.65(j)(1)) rests on prejudicial legal or factual error.11 Borgess contends that the ALJ "fail[ed] to consider" information on its website (Borgess.com) that, according to Borgess, shows that the clinics were held out to the public in accordance with section 413.65(d)(4). B. Reply Br. at 5, 6-9. The ALJ did consider the cited Borgess.com webpages but found the information on them had "little probative value"

Page 33

because there was "no evidence that any . . . patients at the Mattawan, Richland, or Three Rivers locations, check Borgess's website to learn that those locations are operated by [Borgess] so that they are aware of that fact upon entry." ALJ Decision at 9. We need not address whether that was a valid reason for discounting the website evidence because it does not help Borgess in any event. Borgess points to a webpage announcing the 2010 opening of the Mattawan clinic, emphasizing that the page's banner included the Borgess wordmark and a photograph of Borgess Medical Center.12 B. Reply Br. at 7-8 (citing B. Ex. 23). However, any impression created by the banner and photograph about the connection between Borgess Medical Center and the Mattawan clinic was muddled or obscured by the underlying announcement. The announcement identified the Mattawan clinic as "ProMed Physicians – Family Practice"; indicated that ProMed Physicians – not Borgess Medical Center – "ha[d] opened" the clinic; stated that the clinic was an "affiliate" of the Borgess Health network, not that it was a subordinate or integral part of the hospital; and explained that "Borgess Health" is a "health system" that "include[d] Borgess Medical Center," other hospitals, hospice and home health providers, and "many additional owned or affiliated services" without indicating that the Mattawan clinic was connected to any particular Borgess provider.13 B. Ex. 23. The Mattawan clinic – and the other two clinics at issue here – continued to be identified as Borgess Health "affiliates" on Borgess's website as late as September 2014.14 See CMS Ex. 7, at 1 (September 4, 2014 screenshot of Borgess.com webpage stating that "ProMed Physicians – Family Practice is an affiliate of Borgess Health" and identifying the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics as ProMed Physicians locations). In short, the record shows that, from 2009 through September 2014, those clinics were depicted on Borgess.com as autonomous or freestanding facilities within the Borgess Health network, rather than as integral and subordinate parts of Borgess Medical Center.

Borgess also unpersuasively argues that the signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics met the regulatory standard even though they did not contain the main provider's name. Emphasizing that the signs all displayed the "Borgess"

Page 34

wordmark, which it calls an "important distinctive branding tool," Borgess suggests that CMS's finding with respect to the Portage clinic that "local residents closely associate the stand-alone name ‘Borgess' with the hospital [Borgess Medical Center]" (CMS Ex. 1, at 3) applies equally to the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics and demonstrates that the wordmark "in isolation" informed the public that the clinics were part of Borgess Medical Center. B. Reply Br. at 9. The problem with this argument is that the signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not use the Borgess wordmark "in isolation." Rather, they used the wordmark to identify the healthcare network of which the clinics and Borgess Medical Center were a part. The argument also wrongly implies that CMS found the Borgess wordmark on the sign outside the Portage clinic to be sufficient evidence of that clinic's compliance with section 413.65(d)(4). CMS found the Portage clinic compliant based on multiple factors, including: (1) acceptance of Borgess's claim that "local residents closely associate[d]" the stand-alone name "Borgess" with Borgess Medical Center; (2) the "primary and prominent use" of the Borgess wordmark on the sign outside the clinic; and (3) "other evidence tying the [clinic] to the main provider." CMS Ex. 1, at 3. Borgess does not allege, and the evidence of record does not show, that these factors all applied equally to the other three clinics. Most notably, Borgess does not allege or cite evidence that persons living near, or otherwise likely to use, the Mattawan, Richland, and Three River clinics "closely associate[d]" the Borgess name with Borgess Medical Center in Kalamazoo. In addition, those clinics all had exterior signs that did not make "primary" and "prominent" use of the stand-alone "Borgess" name. To the contrary, and as the ALJ noted, the signs outside those clinics "muddie[d] the waters" (ALJ Decision at 14 n.6) by using the Borgess wordmark in conjunction with the words "Health" or "Health Alliance."

Borgess further contends, unpersuasively, that the ALJ's analysis – in particular, the ALJ's refusal to find the clinics compliant with the public awareness requirement based on evidence of what information patients saw or received inside the clinics – is inconsistent with PM A-03-030. See B. RR at 8-9; B. Reply Br. at 10-11. We see no inconsistency or improbability in the ALJ's interpretation of the guidance in PM A-03-030. As the ALJ noted, section 413.65(d)(4), not the program memorandum, provides the governing legal standard, and the program memorandum does not establish a relevant binding rule or purport to interpret language in the regulation. ALJ Decision at 11 ("The CMS program guidance establishes no rule, but merely provides some examples of evidence that may be considered in concluding a facility may or may not meet the public awareness requirement."). Nor does the memorandum specify any set of circumstances in which the public awareness requirement would be considered satisfied. The memorandum merely gives "examples" of "documentation" that may be "maintain[ed]" by a facility to show that the facility is "clearly identified as part of the main provider." CMS Ex. 19. Borgess seizes on one example – "patient registration forms" – implying that CMS would not have mentioned such material if information provided to patients inside the facility could not be used to demonstrate the facility's compliance with the regulation. B. Reply Br. at 11; see also B. RR at 9 ("The only way that the ALJ's

Page 35

decision could coexist with [PM A-03-030] would be for all of the provider-based facility's patient registration forms and letterhead to be made available to patients outside of the facility."). However, nothing in the program memorandum supports Borgess's implication that information provided to patients inside a facility renders that facility compliant with section 413.65(d)(4) regardless of how the facility is "held out to the public" beyond its walls. If anything, the memorandum's examples of supporting documentary evidence suggest that CMS expects any method, or all methods, used to communicate a provider-based facility's identity to the public must comply with the regulatory standard.

B. The ALJ's conclusion that the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement prior to October 2, 2015 is consistent with Board precedent.

Borgess contends that the ALJ's conclusion that its off-campus clinics did not meet the public awareness requirement cannot be squared with the analysis or holdings in Johns Hopkins.15 In that case, HCFA claimed that the Green Spring Oncology Center (GSOC) did not meet Criterion 7 of PM A-96-7 (the public awareness standard superseded by section 413.65(d)(4)), and thus failed to qualify as a provider-based entity of Johns Hopkins Hospital, because bills sent to GSOC's patients did not indicate that they had been sent by the Hospital and instructed that payment be made to GSOC rather than to the Hospital. DAB CR598, FFCL (Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law) 2.d. Based on those circumstances, HCFA argued before an ALJ that patients "would not reasonably assume" that GSOC was part of the Hospital but would instead assume that it was a "separate entity." Id. The ALJ rejected that argument, reasoning that "[a]lthough the billing documents d[id] not specifically refer to the Oncology Center as being part of the Hospital, neither d[id] they state or suggest that the Oncology Center [was] an entity that [was] run separate and apart from the Hospital." Id. The ALJ also observed that the bills sent to patients referred to GSOC as "Johns Hopkins at Green Spring Station" (or "Johns Hopkins at Greenspring") and that "[a] reasonable patient could easily infer from this designation that he or she was being treated by a facility of the Hospital because both the Oncology Center and the Hospital are identified in the public mind with the prefix ‘Johns Hopkins.'" Id. In addition, the ALJ found that any ambiguity presented by the billing documents was "more than cleared up by additional information which [GSOC] and the Hospital communicated to patients."16 Id. Finally, the ALJ found that the "the manner in

Page 36

which the Hospital and [GSOC] treat[ed] . . . patients provided the[m] . . . with a clear indication that the two entities [were] wholly integrated." Id. (noting that GSOC patients were registered as patients of the Hospital, assigned Hospital identification numbers, and given a choice between receiving care at the Oncology Center or at the Hospital). The Board affirmed the ALJ's conclusion that Criterion 7 was met, finding substantial evidence that GSOC "[did] hold itself out as part of the Hospital" and noting that HCFA's analysis "fail[ed] to consider the evidence as a whole." DAB No. 1712, at 12. The Board also agreed with the ALJ that the lack of the word "Hospital" in GSOC's name was insufficient evidence of noncompliance with Criterion 7. Id.

Borgess contends that references to the Borgess Health network on signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics are not problematic in light of the significance attached to the hospital's name in Johns Hopkins. Borgess suggests that the Board in that case found the name "Johns Hopkins" sufficient to identify the Green Spring Oncology Center as part of Johns Hopkins Hospital (the provider). B. RR at 10 (stating that the Board "agreed" with the finding that "‘a patient could reasonably infer . . . that he or she was being treated by a facility of the Hospital because both the Oncology Center and the Hospital are identified in the public mind with the prefix ‘Johns Hopkins'" (quoting DAB CR598, FFCL 2.d)); B. Reply Br. at 10 (asserting that the ALJ in Johns Hopkins found that the Hopkins name "sufficed" to identify the oncology center as part of the hospital). Borgess submits that the Board should likewise find the "Borgess" name sufficient to identify the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics as parts of Borgess Medical Center, notwithstanding that name's pairing with the words "Health" or "Health Alliance." B. Reply Br. at 10.

These points omit or misstate certain details about Johns Hopkins that weaken its force as relevant precedent. As an initial matter, in our view, the names "Johns Hopkins at Greenspring" and "Johns Hopkins at Green Spring Station" are far more suggestive of a provider-based relationship than the references to the Borgess Health network on the signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics. Assuming that the public primarily identified the name "Johns Hopkins" with a hospital (as the ALJ in that case found), rather than with a healthcare network, the formulation "Johns Hopkins at Greenspring" or "at Green Spring Station" indicates that the hospital ("Johns Hopkins") was operating, on an inpatient or outpatient basis, "at" the named location (Greenspring). In contrast, the signs outside the Mattawan, Richland, and Three Rivers clinics do not indicate that "Borgess," the hospital, was operating at those sites, only that some parts of the Borgess Health network of facilities, namely the ProMed physician practices, were situated there.

There is also no indication that the names "Johns Hopkins at Green Spring Station" and "Johns Hopkins at Green Spring" were "advertised" (as Borgess says) to the public; those names appeared only on post-service bills sent to the oncology center's patients. In addition, contrary to Borgess's suggestion, the Board did not hold that the name "Johns

Page 37

Hopkins" was sufficient proof of compliance with the then-existing public awareness standard; the Board indicated only that, given the "longstanding association of the name ‘Johns Hopkins' with the Hospital," the "mere absence of the word Hospital'" in the facility's names (as shown on patient bills) was insufficient proof of failure by the oncology center to hold itself out as part of the hospital. DAB No. 1712, at 12. Also, the Board in Johns Hopkins acknowledged that, in the then-current "healthcare environment," the name "Johns Hopkins" referred not only to the hospital but also to the "Johns Hopkins Health Systems," creating "ambiguity" about whether a facility was part of the hospital or merely a part of the Johns Hopkins Health Systems network. Id. at 13. That ambiguity also exists with respect to the clinics at issue in this case because the record shows that the name "Borgess" was used to identify not just Borgess Medical Center in Kalamazoo, Michigan (the ostensible main provider), but other hospitals and facilities as well as a healthcare network that included Borgess Medical Center and the clinics. CMS Ex. 13, at 1 (explaining that "Borgess Health is a health system" that "includes Borgess Medical Center," other hospitals, and "many additional owned or affiliated services"); CMS Ex. 17, at 113 (notes to consolidated financial statement for the year ending June 30, 2012) (indicating that "Borgess . . . is a nonprofit health system comprising Borgess Medical Center, Lee Memorial Hospital Corporation, Promed Healthcare [and others]").