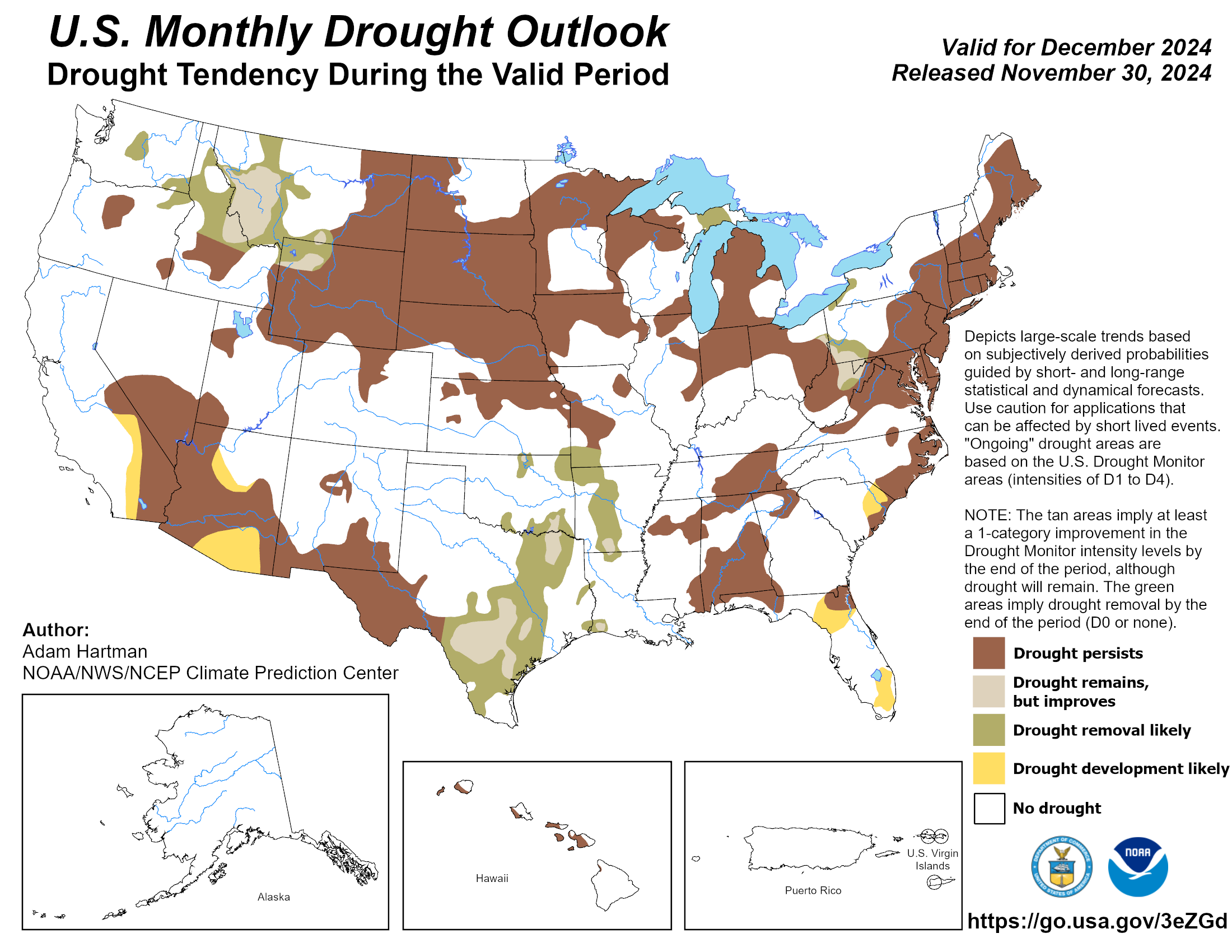

Drought Outlook for December 2024

Figure: The National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center's Monthly Drought Outlook is issued at the end of each calendar month and is valid for the upcoming month. The outlook predicts whether drought will persist, develop, improve, or be removed over the next 30 days or so. For more information, please refer to drought.gov.

Following a wet November, drought coverage has improved across much of the Pacific Northwest, Great Plains, Mississippi Valley, and Great Lakes. Conversely, drought conditions have continued to worsen and expand across portions of the Southwest, Rio Grande Valley, Northern High Plains, and the East Coast states. Through the middle of December, drought persistence is forecast to be favored across the U.S. Drought development is also favored in the southwestern and southeastern U.S. Wetter than average conditions are favored across portions of the south-central and northwestern CONUS, forecasting potential drought improvement and removal. During the second half of December, temperature and precipitation patterns are uncertain.

Drought Affects Health in Many Ways

Drought increases the risk for a diverse range of health outcomes. For example:

- Low crop yields can result in rising food prices and shortages, potentially leading to malnutrition.

- Dry soil can increase the number of particulates like dust and pollen that are suspended in the air, which can irritate the bronchial passages and lungs.

- Dust storms can spread the fungus that causes coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever).

- If there isn’t enough water to flow, waterways may become stagnant breeding grounds for disease vectors like mosquitos as well as viruses and bacteria.

- Drought's complex economic consequences can increase mood disorders, domestic violence, and suicide.

- Long-term droughts can cause poor-quality drinking water and leave inadequate water for hygiene and sanitation.

Dust is made up of small solid particles called particulate matter. The small particles found in dust storms can enter the lungs and damage lung tissue. Dust storms occur when particles blow so thickly that it is hard to see the other side of the road. Dust storms can carry particles that include minerals, allergens, organic matter, and environmental pollutants that can be dangerous when inhaled. Exposure to particles carried by dust storms can therefore worsen or cause health problems such as allergies, asthma, acute bronchitis, sinus infections, valley fever, and pneumonia.

Dust storms can last from just a few hours to a couple of days. They are the most common in the southwestern U.S. and occur most frequently during the spring and summer. The occurrence of dust storms in the U.S. has increased since 1993. Our changing climate is predicted to further increase the frequency and spread of dust storms around the world.

Prevention tips for minimizing health impacts during dust storms:

- Stay indoors as much as you can;

- If you must go out, minimize your time outside and avoid strenuous activity; and

- Cover your nose and mouth with a NIOSH-approved N95 respirator to protect against inhaling large particles.

Individuals facing the highest risk of health problems from exposure to dust storms include infants, children, and teens; older adults; people with asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, or other respiratory conditions; people with heart disease; pregnant individuals; and healthy adults working or exercising vigorously outdoors (for example, agricultural workers, construction workers, and runners). While inhaling large particles can be avoided by covering your nose and mouth, small particles can still enter your respiratory system, making it the most harmful. Therefore, anyone at risk of exposure to dust storms should take precaution. Stay informed about your local air quality conditions and follow your local health public health guidelines.

HHS recently announced the Phase 2 winners of the Environmental Justice Community Innovator Challenge. Over the course of the two-phase challenge, HHS has awarded $1 million dollars to 22 community-driven projects across the U.S. that address environmental justice and public health issues in areas that are being disproportionately impacted by environmental and climate-related hazards. Phase 1 of the Challenge was focused on designing innovative ideas to address environmental health disparities, and descriptions of all Phase 1 Challenge winners were released earlier this year.

Phase 2 of the Challenge was focused on testing and implementing community-led efforts to address environmental health disparities and increase health equity. One Phase 2 winner, Urban Harvest STL, will use their award to address public health issues in St. Louis, MO, by increasing equitable access to healthy food, providing urban farming training, and environmental justice education. Executive Director of Urban Harvest STL, Katie Houck, said, “Urban Harvest STL transforms neglected and abandoned urban spaces into thriving ecosystems. We use these spaces to ignite children’s curiosity about the environment and where their food comes from. Our farms are living classrooms where aspiring farmers learn to grow healthy food for their communities. They bring together neighbors, cultivating a sense of unity and shared purpose.” Descriptions of all Phase 2 Challenge winners were released in September.

People at elevated health risk from drought exposure according to NIDIS & CDC include those who:

- Have increased exposure to dust (e.g., are experiencing homelessness and/or work outdoors);

- Rely on water from private wells and small or poorly maintained municipal systems, the quality of which is more susceptible to environmental changes;

- Work in agriculture and/or live in an agricultural community;

- Have increased biologic sensitivity (e.g., are under age 5, are age 65 or over, are pregnant, and/or have chronic health conditions such as a mental illness or a respiratory disease); and/or

- Have special needs in the event of a public health emergency.

Drought is a slow-moving climate disaster with both direct and indirect impacts on mental health. Farmers and their families are of particular concern because drought affects their jobs and livelihoods which in turn leads to stress and other health impacts. A recent study looking at the association between drought exposure and the risk of death by suicide in the United States from 2000 to 2018 found an association between all drought types and increased firearm suicides among U.S. farmers – the more severe the drought, the greater the association. A systematic review identified additional vulnerable populations for the impact of drought on mental health including rural or remote populations and indigenous populations. A few of the factors that can be exacerbated by drought and lead to anxiety and/or depression are struggling economies, migrations of community members, feelings of humiliation, household tension, and increased workloads.

Figure: Keep It Together by Tammy West. Artist’s statement: Texas and much of the Western United States have been experiencing climate change-induced severe drought. This site-specific piece focuses on our collective climate grief.

Valley fever, also called coccidioidomycosis, is a fungal disease that can affect people who breathe in the microscopic fungal spores in areas where the fungus lives in the environment. Roughly 15,000–20,000 Valley fever cases are reported each year to the CDC, but it is thought that the true number of infections is much higher. Some people who are exposed to the fungus never get sick, but others may develop symptoms similar to other lung infections (e.g., cough, fever, shortness of breath). In some cases, the infection may spread to other parts of the body, which often results in hospitalization and prolonged antifungal treatment. In endemic areas, Valley fever can cause up to a third of community-acquired pneumonia cases.

Figure. Estimated areas with Valley fever in the United States from CDC. Darker shading shows areas where the fungus that causes Valley fever is more likely to live but geographic boundaries are not strictly defined and may change over time.

Climate Change

Coccidioides, the fungus that causes Valley fever, lives in soil in hot, dry regions, and its geographic range may be expanding because of climate change. Traditionally, the fungus has predominantly been found in the southwestern U.S., but more recently, in 2015, it was detected as far north as Washington state. As temperatures increase, more areas may offer conditions favorable to the growth and dispersal of the fungus. Experts predict that Coccidioides’ endemic range in the U.S. could more than double by the year 2100. Valley fever rates are also affected by rainfall and drought cycles; in California, researchers found that incidence increased after long periods of drought followed by wet winters. These patterns are expected to become more common and, widespread, and to intensify with the changing climate. Severe weather events such as dust storms and wildfires are becoming more frequent and have also been linked to Valley fever, although the exact nature and extent of the associations is unclear.

Figure: Fungal diseases may increase through a variety of mechanisms as temperatures rise worldwide (infographic by CDC). Valley fever is impacted by some, but not all, of these mechanisms as temperatures rise and its geographical range expands.

Health Equity

Anyone can get Valley fever if they live in or travel to an area where the fungus lives, but certain populations, such as those with weakened immune systems, are at greater risk for developing severe illness. Some racial and ethnic minorities also appear to be at greater risk of Valley fever in the U.S.: American Indian and Alaska Native and Hispanic populations have more than twice the rate of Valley fever compared with White populations. Although the reasons for these health disparities are unclear, they are likely influenced by social determinants of health, such as housing conditions and access to healthcare. People with certain occupations, particularly outdoor jobs, also have higher rates of severe Valley fever. A survey of Hispanic farm workers found that self-reported exposures to dust and root and bulb crops were linked to increased incidence of Valley fever, though the relative impact of occupation compared with ethnicity on infection was unclear. Outbreaks among firefighters have also been reported, particularly among those that use hand tools and work in dusty conditions in areas where Coccidioides lives.

Prevention

Valley fever is difficult to prevent in areas where the fungus lives since the disease is acquired directly from the environment. There are currently no feasible methods to remove the fungus from the environment. To help prevent Valley fever, people can avoid spending time in dusty places and avoid participating in activities that disturb dust in areas where the fungus is endemic. If these activities are unavoidable, an N95 mask should be worn; in occupational settings, appropriate training and personal protective equipment should be provided to workers to help prevent illness and monitor for symptoms. Staying inside and closing windows during dusty days and using air filtration indoors may also prevent Valley fever. Cleaning injuries exposed to dust or dirt well with soap and water is also useful to inhibit cutaneous infection.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment can prevent severe disease. Unfortunately, Valley fever awareness is low, even in areas where the fungus lives. It is important to increase awareness so that people understand when to seek healthcare. Healthcare providers can use CDC’s clinical diagnostic algorithm to assist in recognizing who and when to test for Valley fever.

Figure: This map shows the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) values for the U.S. from January 1, 2023–December 31, 2023. The DSCI is an experimental method for converting drought levels from the U.S. Drought Monitor map to a single value for a county.

The year 2023 was the 3rd driest for the contiguous U.S. on record. From January 1, 2023 - December 31, 2023, the majority of the U.S. experienced some level of abnormal dryness as measured by the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI). The DSCI values range from 0 to 500, where 0 means that none of the area was on average abnormally dry or in drought, and 500 means that all of the area was on average in exceptional drought. The Northwest, Midwest, Northern Great Plains, and Southern Great Plains generally had the highest levels of drought. 23 U.S. counties (six in Kansas, ten in Nebraska, and seven in Texas) had DSCI values in the highest range (>400), meaning they experienced exceptional drought. Additional counties in those states along with one in Oklahoma ranked in the top 50 for drought in the past year. Only 18 out of the 3,231 counties for which we have measurements experienced an average DSCI value of zero.

Climate change is affecting the frequency and severity of both flooding and drought in many areas of the US. Both conditions pose potential risks for well water, which are important considerations for healthcare and public health. To better understand the implications for families, we consulted Dr. Alan Woolf, an internationally-recognized environmental toxicologist, a practicing pediatrician for nearly 40 years, and a part of the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital. In counseling families who have private wells, he has seen firsthand how climate-related hazards affect drinking water safety.

Flooding

Flooding is a common cause of private well contamination with bacteria and other pollutants that can cause illness. Rapidly flowing flood water can carry large debris that hits wells, loosening or dislodging well hardware, while coarse sediment in the flood water can erode pump components. If the well is not tightly sealed, the sediment and flood water can enter the well and contaminate it. Floods may even cause some wells to collapse.

“Well water quality has been a concern for my patients’ families throughout the Northeast due to major flooding in the summer of 2023. I recently cared for a patient who was having neurologic symptoms whose family discovered that their leaves had a coppery sheen – it turned out their well cap had been breached during recent flooding and their well water was contaminated with manganese, which was the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Another child in my care had gastrointestinal symptoms after a flooding event – the family had their well water inspected and it showed high coliform bacteria, increased metals, and other evidence of contamination.” - Dr. Woolf

Drought

During a drought, aquifers can get depleted from overextraction and inadequate replenishment, leading to a lack of potable water for families with wells. In addition, drought conditions can change the dynamics of groundwater, potentially leading to natural contaminants flowing into the water from bedrock such as arsenic, which can be harmful to health with chronic exposure. You can read more about these concerns from USGS: Groundwater Decline and Depletion and Drought May Lead to Elevated Levels of Naturally Occurring Arsenic in Private Domestic Wells.

“Water quality concerns are elevated when children are drinking from private wells. I recommend my patients’ families with private well water get their water tested regularly and be aware of these extra challenges during times of flooding and drought.” - Dr. Woolf

Resources to protect well water

While EPA does not regulate private wells, they do offer guidance to private well owners. To help protect your well during times when it may flood, make sure you can see and access your well cap to assess threats. Even without obvious damage, wells that are more than 10 years old or less than 50 feet deep are likely to be contaminated during a flood. If you suspect your well has been contaminated, EPA provides specific recommendations for well owners to follow in its short guide What to do After the Flood, and CDC provides recommendations for Disinfecting Wells After a Disaster.

The EPA does not have specific guidance for private wells during drought, but they recommend testing private wells annually (or more frequently if small children, elderly adults, or somebody who is pregnant or nursing is drinking the water, as these segments of the population have elevated vulnerability to pollutants), immediately after significant flooding and other nearby activities, and if there are signs of drought impacts such as a change in taste or color of the water, sputtering faucets, sudden pressure changes, or air bubbles.

Dr. Woolf has also co-authored a policy statement for the American Academy of Pediatrics on Drinking Water From Private Wells and Risks to Children.

Figure: Map showing the probability of having arsenic >10 μg/L (“high arsenic”) in domestic wells during drought. Arsenic occurs in groundwater due to chemical reactions between the rocks and water, lowering of water levels due to drought may cause chemical changes that release more arsenic from the rocks. Less water could also concentrate existing arsenic in the water. Hotspots generally reflect areas in the U.S. with high observed concentrations including New England (predominantly Maine and New Hampshire), a band in the upper Midwest, the southwest (most notably Nevada, southern Arizona, southern and central California, and isolated regions in all western states), and southern Texas.

Drought conditions can lead to elevated levels of naturally occurring arsenic in the water we drink. The risk of contamination increases the longer that a drought persists. In a study done by U.S. Geological Survey and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021, researchers estimated that over 9% (4.1 million) of the 44.1 million people in the lower 48 states who use private domestic wells were potentially exposed to unsafe levels of arsenic during drought conditions compared to about 6% (2.7 million people) during non-drought conditions. Chronic exposure to arsenic from drinking water is associated with an increased risk of several types of cancers, developmental issues, cardiovascular disease, adverse birth outcomes and impacts on the immune and endocrine systems.

While summer is the peak for extreme heat, climate change has led to an increase in several hazards in the fall. Fall temperatures have increased by about 1.6°F on average across the contiguous 48 states compared to the 1901–2000 baseline. An increase of this magnitude has led several areas in the U.S. to experience extreme heat days into the fall season. Warmer fall temperatures extend the growing season, which can lead to a more intense fall pollen season for allergy sufferers, as well as extend the active season for mosquitoes and ticks, which can lead to increased transmission of vector-borne diseases in the fall. In regions with low precipitation during the summer, drought conditions can worsen during the fall. Fall can also bring increased wildfire risk due to dry conditions (i.e., dry vegetation from hot summer weather plus delayed onset of winter rains) and strong winds (e.g., the Santa Ana and Diablo winds in California and the Chinook winds in the Rockies). The Atlantic hurricane season also peaks in the fall, and warmer ocean temperatures can lead to more intense and frequent storms.

Local conditions can be monitored using:

- the CDC-NWS HeatRisk Forecast Tool for a forecast of when temperatures are expected to reach potentially harmful levels for health in the next seven days;

- the new edition of the EPA’s Fire & Smoke Map for the current air quality and whether it is stable, improving, or getting worse;

- NOAA's U.S. Drought Monitor for the location and intensity of drought across the country; and

- NOAA’s Seven-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook for short-term hurricane forecasts.

Resources to Reduce Health Risks Associated with Drought

Drought poses many and far-reaching health implications. Some drought-related health effects occur in the short-term and can be directly observed and measured. But the slow rise or chronic nature of drought also can result in longer term, indirect health implications that are not always easy to anticipate or monitor.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Drought and Health site and Ready.gov Drought site have information on the health implications of drought and how to prepare. The U.S. Drought Portal provides data, decision-support products, resources, and information on drought.

Image source: https://www.cdc.gov/drought-health/media/pdfs/CDC_Drought_Resource_Guide-508.pdf

The Department of Agriculture offers programs that can help with drought recovery as well as those that can help farmers manage risk and build resilience. The Department’s Climate Hubs feature regional resources including vulnerability assessments and tools and a Climate, Agriculture, and Forest Science Webinar Series.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is an online, weekly map showing the location, extent, and severity of drought across the United States. The Department of Agriculture uses the Drought Monitor to determine a producer’s eligibility for certain drought assistance programs. You can report drought-related conditions and impacts within the U.S. and associated territories to the Drought Monitor.

The Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service can help farmers conserve water and build resilience to drought, through conservation practices that improve irrigation efficiency, boost soil health, and manage grazing lands.

Image source: https://www.farmers.gov/blog/making-your-land-more-resilient-drought

Drought is a slow-moving hazardous event, so the psychological effects of living through this type of disaster are more subtle and last longer than with other natural disasters. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Helpline and Text Service is available 24/7, free, and staffed by trained crisis counselors. Call or text 1-800-985-5990 to get help and support for any distress that you or someone you care about may be feeling related to any disaster.

Funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy within the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Rural Health Information Hub offers several resources about drought and other stressors farmers face, as well as information and resources about farmers' mental health and prevention of suicide among farmers.

Learn more about drought and mental health at the SAMHSA’s Drought site. SAMHSA also has other disaster behavioral health resources, including newsletters and tip sheets. Check out SAMHSA’s newly launched Climate Change and Health Equity site for more information on the behavioral health impacts of climate change, preparing for a disaster, and resources for disaster planning and climate change education.

OCCHE’s Referral Guide summarizes resources that can address patients’ social determinants of health and mitigate health harms related to climate change. These resources include social services and assistance programs to which patients can be referred, as well as references for anticipatory guidance and counseling to help patients prepare for potential hazards.

Navigate to our other climate hazard pages below: